Fake News

Lucius Verus, brother of Marcus Aurelius and co-ruler of the Roman Empire from AD 161 to AD 169, was undoubtedly the victim of ‘fake news’, which Wikipedia defines in the following manner:

Fake news is written and published with the intent to mislead in order to damage an agency, entity, or person, and/or gain financially or politically, often using sensationalist, dishonest, or outright fabricated headlines

This perfectly describes what the later sources have done with Lucius Verus. We have grown used to the phenomenon in the second decade of the 21st century, but few have questioned whether Lucius was also the victim of a similar process. Comparison of the surviving contemporary sources with the later, more scurrilous ones suggests that caution is necessary in believing what we are told.

For our purposes, the most prominent purveyor of fake news about Lucius (and, indeed, many other emperors) is the series of biographies nowadays known as the Historia Augusta. This purports to be a series of imperial biographies by different authors, although stylistic analysis of the text has shown that there is just one author behind the whole thing. The very concept of the Historia Augusta is thus fake news insofar as it is a deliberate deception, so it is unsurprising that its content is questionable in places. This has long been recognised by modern scholars, but what is strange is the degree to which they have bought into the version of Lucius Verus provided by the Historia Augusta and not sought to compare it to contemporary writers. Indeed, many have instead looked for reinforcement in those earlier writings and generally found it, whether it is truly there or not.

Examining Lucius’ letters to his brother Marcus Aurelius and to his tutor, Cornelius Fronto, show a very different man to the one depicted in the Historia Augusta. He is a little vain, certainly, but concerned to do the right thing and to be seen to be doing it. The view of Lucius preserved in Marcus’ Meditations, a commonplace journal never intended for publication, shows just how much he valued him.

There is now active campaigning to raise awareness of fake news and to attempt to make readers more questioning of what they are expected to believe. Ironically, this has long been the goal of the discipline of ancient history, where source criticism is one of the first things students are taught. The study of the past is all too relevant to modern, everyday life.

Intended Heir

We see Lucius Verus through such a distorting lens that it is difficult to be sure how the ‘succession crisis’ of Hadrian should be interpreted. His ultimate choice for adopted successor, Lucius Ceionius Commodus (the man who became Aelius Caesar), died soon after being selected. His natural son, also Lucius Ceionius Commodus, was then adopted (along with Marcus Aurelius) by the man who would become known to posterity as Antoninus Pius at the same time as Hadrian adopted him as Aelius Caesar’s replacement. If this appears as confusing and haphazard, imagine how the people of Rome felt! Young Lucius is shown on the so-called Parthian Monument (a piece of post-mortem pro-Lucius propaganda) with Hadrian’s arm around his shoulders, whilst Marcus stands to one side, a gangly youth with big hair and great prospects. Is there a message in there? Was it being signalled that Lucius was really Hadrian’s intended heir and that Antoninus Pius was the bridge to making that happen? Pius’ alleged favouritism towards Marcus served to negate this, if it was ever the case, but that partisanship towards Marcus was in turn foiled by Marcus’ own surprising move of asking his adoptive brother to be co-emperor on the day of his (not their) accession. It is always important to remember the curious fact that Hadrian made Pius adopt both boys, but only Marcus received the endorsement of the Senate, and ask ‘why?’.

Playboy

Lucius’ reputation as a fun-loving playboy is well known and recounted in loving detail in the Historia Augusta. The problem is that our contemporary sources do not support the hedonist portrayed in that source. Like many other aristocrats in the Roman Empire, he certainly seems to have enjoyed the good life, but there is nothing that suggests he neglected his duties in favour of the search for fun. In other words, it looks as if he has been the victim of wholesale exaggeration by his later biographer and it was that which was used by the Historia Augusta. Blackening his name served no purpose in the 4th century AD, so the smears must have been applied earlier, whilst his memory was fresh enough to lend some credence to it. After all, as we all now know only too well, and as Goebbels apparently did not say, if you repeat a lie often enough, people will believe it, and you will even come to believe it yourself.

General

The Historia Augusta makes great play of the fact that Lucius did not conduct his two major campaigns in the East from the front line, but rather chose to remain in Antioch for most of the time. What it neglects to mention is that most emperors who got involved in warfare also kept well clear of the action, but by highlighting the fact that Lucius did the same, it sought to make him look unwarlike. In fact, an emperor who could not resist the temptation to get ‘stuck in’ ran the risk of capture (as happened to Valerian in AD 260) or death (the fate of Decius in AD 251 and, possibly, Gordian III in AD 244), so it could be argued that a frontline general was a positive hindrance, rather than an asset to an army on campaign.

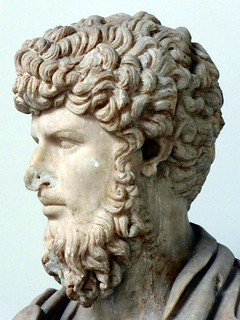

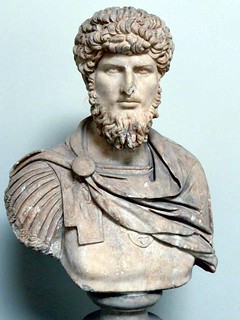

The Look

Lucius was very particular over his appearance. He had blonde hair and the later sources say he liked to enhance it with gold dust, although there is no contemporary confirmation for this. His portrait busts do suggest he consciously imitated his biological father’s facial hair, but that is scarcely a cause for approbation. The sources make much play of his vanity, so it is possible there was an element of truth at its root which, as with everything else, was subject to exaggeration.

The Truth

The truth may be ‘out there’, but it is difficult to pin down. Lucius Verus was no saint (but then nobody is or was, even genuine, card-carrying saints), but neither was the extreme portrait painted by the later sources likely to be true. The truth about him lies somewhere in between and in my book I offer a suggestion for ‘who dunnit’. In the end, the best assessment of Lucius Verus the man probably comes from his adoptive brother:

I thank the gods for giving me such a brother, who was able by his moral character to rouse me to vigilance over myself, and who, at the same time, pleased me by his respect and affection. (Marcus, Med. 1.17)

My book, Lucius Verus and the Roman Defence of the East, is available from Hive, Amazon, and direct from Pen & Sword in the UK, and should be obtainable worldwide through Amazon.